How Oregon state parks evolved from roadside picnic areas into iconic natural landmarks—Blog Article on HERE Places

By Jamie Hale | The Oregonian/OregonLive

Aug. 14, 2022

Beachgoers in 1959 visit the Peter Iredale shipwreck at Fort Stevens State Park on the north Oregon coast. (Oregonian File Photo)

Oregon’s first state park isn’t much. There are no waterfalls, no sweeping views, no interpretive center or historic buildings. Unless you happen live in the area, or are driving past and need to rest, or are collecting state park experiences like rare coins, there’s not much reason to stop by.

One thing Sarah Helmick State Recreation Site does offer is a sense of contrast. It makes you wonder: How did Oregon state parks go from practical roadside picnic areas like this, to the iconic natural landmarks that we now adore?

This year, the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department celebrates the 100-year anniversary of that first state park, taking the opportunity to reflect on the past and consider what parks might look like in the future.

HERE IS OREGON: HereisOregon.com | Instagram | YouTube | Facebook | Twitter | TikTok

During the last century, one thing has become clear: Parks are an integral part of the Oregon experience, woven into the fabric of our state identity like nothing else.

Auto Parks

When 98-year-old Sarah Helmick donated her family’s land to the state of Oregon for a new recreation area, she didn’t contact the state parks department to do it – no such department existed.

A summer picnic at Sarah Helmick State Recreation Site, the first Oregon state park, opened near Monmouth in 1922. (Jamie Hale/Jamie Hale/The Oregonian)

In 1922, parks were the purview of the State Highway Commission, which had recently been empowered to acquire land alongside highways for conversion into recreation areas known as “auto parks.” The advent of the automobile meant more highways across the Pacific Northwest, and subsequently a need for places to stop and rest during road trips.

Christy Sweet, historian and preservation specialist for the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, said parks were initially envisioned as just places to stop for a picnic, a restroom or maybe a good view.

“The whole camping idea wasn’t in the state parks at all,” Sweet said.

Neither were the concepts of hiking, mountain biking, kayaking or rock climbing. In fact, one of the parks’ earliest champions, Samuel H. Boardman, stood staunchly against using parks for recreation at all, Sweet said.

In 1929, Boardman was tapped to helm the new State Parks Commission, which quickly grew the state park footprint from 4,000 acres to 66,000. Under his leadership, the state purchased land that would later become Silver Falls, Oswald West and Ecola state parks, among others. He bought defunct lighthouses that are now iconic landmarks and snatched up surplus military land. His impact was enormous, but Oregon’s state parks remained places to stop and look, not to stay and explore.

In Boardman’s opinion, state parks were meant to be preserved from human impact, and camping was therefore heretical, Sweet said. That changed almost immediately following his retirement in 1950; two years later, Oregon’s first state park campgrounds opened at Silver Falls and Wallowa Lake. People flocked to the new campsites, and within 10 years, some 44 additional campgrounds were developed and constructed around the state.

“It seems to me that peoples’ views of how they want to experience nature and history changes over the years, and state parks change as it goes along,” Sweet said.

Picnickers came from near and far to take part in the 1935 dedication of Ecola State Park in Cannon Beach. The original caption noted: “Automobiles may now drive within a few feet of the park and enjoy a magnificent view of the picturesque Oregon shore line.’ (Oregonian File Photo)

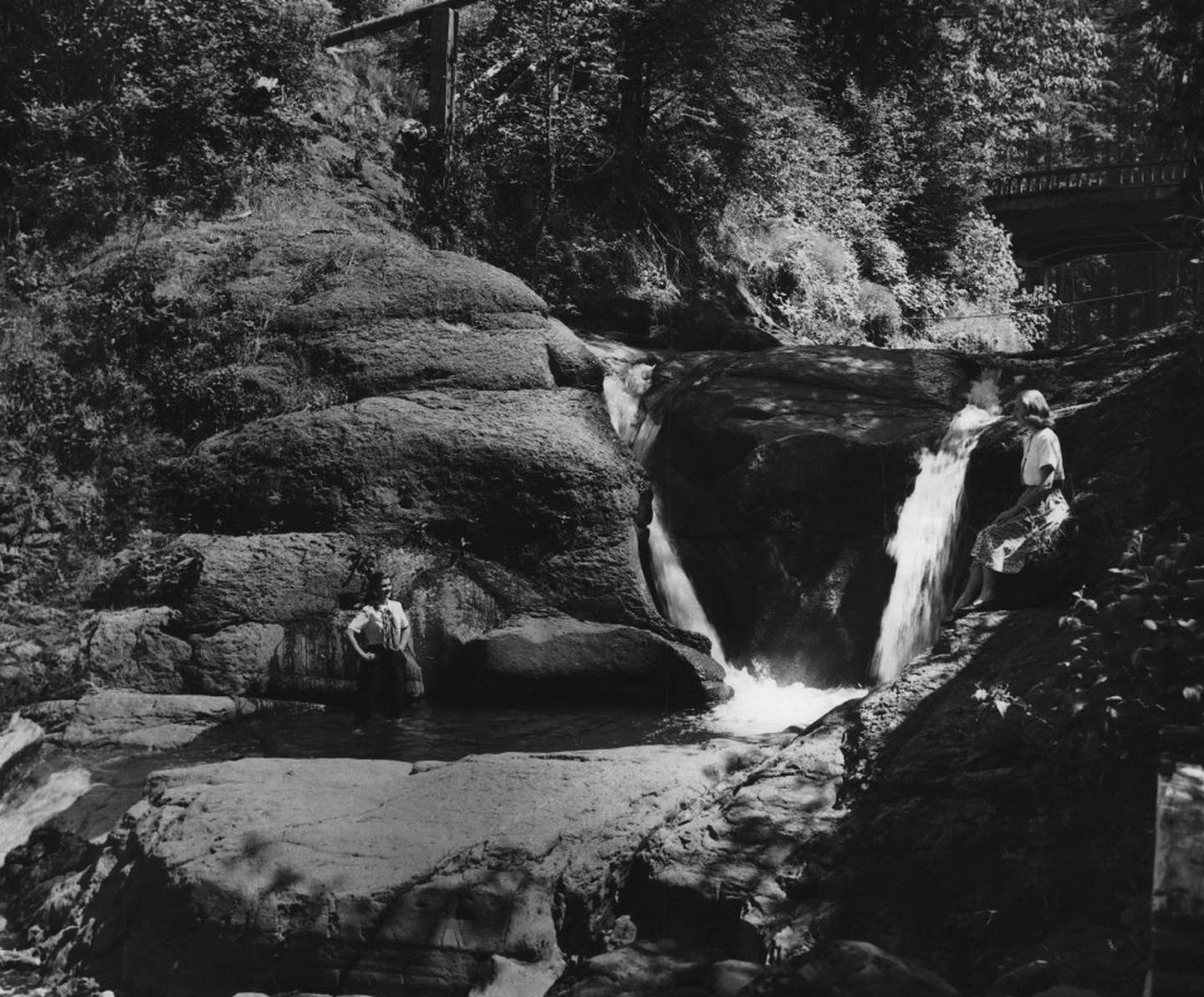

Visitors in 1949 explore Cascadia State Park between Salem and Eugene, a natural area that is now managed by Linn County. (Oregonian File Photo)

The years following World War II saw an increased interest in outdoor recreation, buoyed by the recent standardization of the five-day workweek and the growing middle class. Oregonians suddenly had time and money to explore the state’s natural beauty, and state parks offered easy access and amenities to do just that.

Oregon state parks also benefitted from the environmental movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, which saw a surge in support of ecological causes, especially among the burgeoning counterculture rooted locally in Portland and Eugene. From hippies to hunters, everyone seemed to love their local parks. The only issue was how to fund the upkeep of these beloved places.

As part of the State Highway Commission (which was later folded into the Oregon Department of Transportation), the state parks program was funded primarily through Oregon’s gas tax. In 1980, voters approved a constitutional amendment that limited the revenues of gasoline and highway user tax money, shifting park funding to the state’s General Fund and leaving it more susceptible to economic fluctuations, like the early ‘80s recession.

In 1989, the state legislature created the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, officially cleaving parks from ODOT, but chose not to designate a source of funding, leaving the new department hanging in the wind. No new parks were created, the maintenance backlog grew and some parks contemplated shutting down altogether.

Anecdotes from those years come in various shades of desperation. In one, park rangers planed down old highway signs to make picnic tables. One state park sold Beanie Babies in its gift shop, purportedly raising $100,000 in a year. Managers at a coastal park allegedly considered selling lots for condos, but never got around to it.

“They were looking at any source of funding,” Sweet said. “During the ‘90s it was a terrible time.”

Mountain bikers take laps on a run at L.L. "Stub" Stewart State Park, which includes this wall that volunteers milled from downed forest wood,. (Jamie Francis/The Oregonian)

One of several yurts available at Fort Stevens State Park on the north Oregon coast. (Jamie Hale/Jamie Hale/The Oregonian)

The lean times did lead to one major innovation: yurts in state park campgrounds, which helped lure offseason campers and inspired an international glamping trend that continues today. At state parks, necessity really did prove to be the mother of invention.

In 1998, the parks department finally found relief after voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot initiative that sent a portion of state lottery funds to parks and beaches. The Oregon Lottery remains the primary source of funding for the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department today, along with recreation fees and RV registration fees.

With funding in hand, the department began to address long-neglected maintenance issues and once again began to build new parks. Between 2005 and 2018, the department created eight new parks around the state, including L.L. Stub Stewart in the foothills of the Coast Range, Cottonwood Canyon in the high desert of north-central Oregon, and Iwetemlaykin in the Wallowa Mountains.

That growth and funding came at the perfect time: Oregon’s state parks were about to get a whole lot busier.

A visitor takes a selfie in front of Lower South Falls in Silver Falls State Park. (Jamie Hale/Jamie Hale/The Oregonian)

Instagram Famous

Peter Marbach stood in the halls of the Oregon Historical Society museum, reminiscing about his photos that hung in an exhibit on the walls. To celebrate the state park centennial, the historical society commissioned Marbach to drive around and document as many parks as he could, displaying his photos as part of an exhibit called “A Century of Wonder: 100 Years of Oregon State Parks.”

“How lucky are we to live in a place like this?” Marbach said, eyeing his photos of beaches, waterfalls, mountain snow and desert wildflowers. “It’s pretty miraculous, just that foresight that (Oregon) leaders had to do this, to make it possible for us.”

One thing that makes Marbach’s exhibit so striking is how familiar the pictures have become. Social media feeds are now flooded with photos of Smith Rock, Silver Falls and the many scenic parks on the Oregon coast, as more and more people drive out to visit them.

In 2010, state parks drew a total of 41,498,739 day-use visitors statewide. In 2016 those numbers surpassed 51 million, and by 2022 they eclipsed 53 million people. Overnight numbers saw similar, though less-dramatic trends, increasing from 2.4 million camper nights in 2010 to more than 3 million in 2021.

Park officials acknowledge that those numbers aren’t exact. Day-use numbers in particular are rough estimates based on the number of vehicles counted in parks, multiplied by the average number of people per vehicle. But while they may not be reliable for exact visitor counts, they do give a good idea of the surge in park popularity.

Park officials have attributed the recent popularity to a variety of factors, like the increase in population and difficult economic times. One factor that can’t be ignored is the power of social media, particularly the photo-sharing app Instagram, which debuted in 2010.

Pull up Instagram and you’ll find hundreds of accounts sharing beautiful pictures of Oregon’s natural places, sending them to the feeds of millions of people. State tourism agency Travel Oregon has some 367,000 followers on the app, more than eight times the following of Gov. Kate Brown. The Oregon Parks and Recreation Department has a nice audience as well, with more than 71,000 followers.

When those social media followings translate into real-life visits, Oregon’s natural places have a tendency to get overcrowded, turning once-quiet escapes into busy destinations. That’s left the state parks department with a happy problem: how to manage the throngs of visitors.

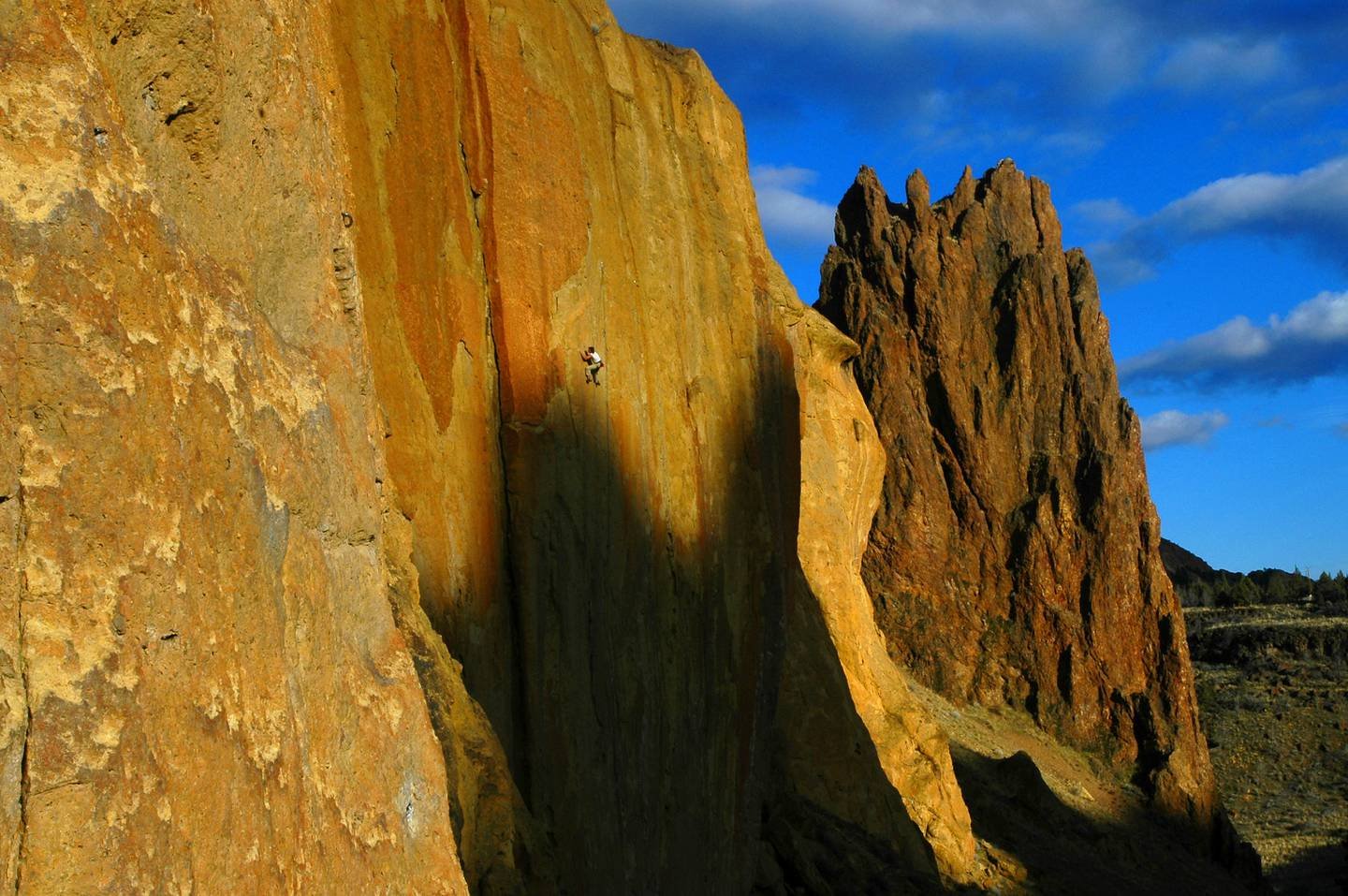

Brian McMillan of Bend climbs the route known as Magic Light in early February at Smith Rock State Park in Terrebonne, Oregon. (Jamie Francis/The Oregonian)

Surfers and beachgoers take a path to Short Sand Beach at Oswald West State Park. Some state park sites on the north Oregon coast reopened to the public Friday, June 5, more than two months after closing due to the coronavirus pandemic. (Jamie Hale/The Oregonian)

Few people are as acutely aware of the crush of crowds as Chris Gilliand, park manager at Silver Falls State Park in Silverton. Considered the “crown jewel” of Oregon’s state park system, Silver Falls is known for its many beautiful waterfalls, seen on the popular Trail of Ten Falls that runs through the park. It also offers a sprawling campground, picnic areas, a resort and a largely unexplored backcountry.

In 2021, a total 1,124,340 day-use visitors and 76,079 campers stopped by Silver Falls, making it one of the busiest outdoor recreation areas in the state.

“I think we’re just on peoples’ list of places to see when you come to Oregon,” Gilliand said. “We’ve probably had somebody here from everywhere in the world.”

The parks department has responded not by limiting the number of people who can visit, but by expanding the area they can go. Silver Falls is in the midst of a massive project building a new campground, parking lot, trailhead and viewpoint on the north side of the park – an attempt to alleviate overcrowding at the primary entrance on the south side. It’s expected to be the most expensive part of a $50 million state park upgrade, which started in 2022.

There’s a similar attempt to ease congestion at Smith Rock State Park, a rock climbing paradise in central Oregon that was once named one of the Seven Wonders of Oregon. There, park manager Matt Davey said the plan was to eventually restructure the parking areas and create more accessible interpretive trails for people who don’t want to hike into the park. A new visitor center is also in the works.

“As natural resource agencies we need to figure out how to accommodate the people and protect the natural resource too,” Davey said. “It may take inventing new ways that we do business.”

Park officials have acknowledged that there are no easy solutions. While the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service have started restricting visitors in some sensitive natural areas with limited permits, the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department has yet to do so. And of the 259 state park sites, only 26 charge parking fees.

The open-door policy is baked into the ethos of Oregon state parks, an organization that from the start has been focused on connecting people with nature. That connection seems one of the biggest reasons people continue to flock to these beautiful places.

“Really what it is, is a stirring of emotions,” Davey said. “It’s something that speaks to your core at a level that’s maybe hard to understand – when you get that raw sense of geologic time, and that makes you feel sometimes that the world is a lot bigger and more magnificent, and moving at a different pace than your day to day.”